Ξ 50º aniversarios Airbus A300 Ξ

AW | 2022 10 30 17:11 | AVIATION HISTORY

Airbus lanzaba su primera gran aeronave

![]()

El primer bimotor de fuselaje ancho del mundo daba un salto hace medio siglo por parte del constructor aeronáutico Airbus Industrie siendo la punta de lanza para el fin del monopolio estadounidense en la aviación comercial. El 28 de Octubre de 1972 realizaba el vuelo inaugural el Airbus A300, el comienzo de la verdadera industria europea que quebraba el duopolio Boeing-McDonnell Douglas.

El Airbus A300 es un avión de fuselaje ancho desarrollado y fabricado por Airbus. En Septiembre de 1967, los fabricantes de aviones en el Reino Unido, Francia y Alemania Occidental firmaron un Memorando de Entendimiento (MoU) para desarrollar un gran avión de pasajeros. Alemania Occidental y Francia llegaron a un acuerdo el 29 de Mayo de 1969 después de que los británicos se retiraran del proyecto el 10 de Abril de 1969. El fabricante aeroespacial colaborativo europeo Airbus Industrie se creó formalmente el 18 de Diciembre de 1970 para desarrollarlo y producirlo. El prototipo voló por primera vez el 28 de Octubre de 1972.

El primer avión bimotor de fuselaje ancho, el A300 normalmente tiene capacidad para 247 pasajeros en dos clases en un rango de 5.375 a 7.500 km (2.900 a 4.050nmi). Las variantes iniciales están propulsadas por turbofans General Electric CF6-50 o Pratt & Whitney JT9D y tienen una cabina de vuelo de tres tripulantes. El A300-600 mejorado tiene una cabina de dos tripulantes y motores CF6-80C2 o PW4000 actualizados; realizó su primer vuelo el 8 de Julio de 1983 y entró en servicio más tarde ese año. El A300 es la base del A310 más pequeño (voló por primera vez en 1982) y fue adaptado en una versión de carguero. Su sección transversal se mantuvo para el A340 (1991) de cuatro motores más grande y el A330 bimotor más grande (1992). También es la base para el transporte Beluga de gran tamaño (1994).

El cliente de lanzamiento Air France introdujo el tipo el 23 de Mayo de 1974. Después de una demanda limitada inicialmente, las ventas despegaron a medida que el tipo se probó en el servicio temprano, comenzando tres décadas de pedidos constantes. Tiene una capacidad similar al Boeing 767-300, introducido en 1986, pero carecía de la gama 767-300ER. Durante la década de 1990, el A300 se hizo popular entre los operadores de aviones de carga, tanto como conversiones de aviones de pasajeros como construcciones originales. La producción cesó en Julio de 2007 después de 561 entregas. A partir de Junio de 2022, había 229 aviones de la familia A300 en servicio comercial.

En 1966, Hawker Siddeley, Nord Aviation y Breguet Aviation propusieron el HBN 100 de fuselaje ancho de 260 asientos con una configuración similar. Durante la década de 1960, los fabricantes de aviones europeos como Hawker Siddeley y British Aircraft Corporation, con sede en el Reino Unido, y Sud Aviation de Francia, tenían ambiciones de construir un nuevo avión de pasajeros de 200 asientos para el creciente mercado de la aviación civil. Si bien se realizaron y consideraron estudios, como una variante bimotor estirada del Hawker Siddeley Trident y un desarrollo ampliado del British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) One-Eleven, designado BAC Two-Eleven, se reconoció que si cada uno de los fabricantes europeos lanzara aviones similares al mercado al mismo tiempo, ninguno alcanzaría el volumen de ventas necesario para hacerlos viables. En 1965, un estudio del Gobierno británico, conocido como el Informe Plowden, había encontrado que los costos de producción de aviones británicos eran entre un 10% y un 20% más altos que sus homólogos estadounidenses debido a las tiradas de producción más cortas, lo que se debió en parte al mercado europeo fracturado. Para superar este factor, el informe recomendó la búsqueda de proyectos de colaboración multinacionales entre los principales fabricantes de aviones de la región.

Los fabricantes europeos estaban dispuestos a explorar posibles programas; el HBN 100 de fuselaje ancho propuesto de 260 asientos entre Hawker Siddeley, Nord Aviation y Breguet Aviation es un ejemplo. Los gobiernos nacionales también estaban dispuestos a apoyar tales esfuerzos en medio de la creencia de que los fabricantes estadounidenses podrían dominar la Comunidad Económica Europea; en particular, Alemania tenía ambiciones de un proyecto de avión multinacional para vigorizar su industria aeronáutica, que había disminuido considerablemente después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A mediados de la década de 1960, tanto Air France como American Airlines habían expresado interés en un avión bimotor de fuselaje ancho de corta distancia, lo que indica una demanda del mercado para que se produjera dicho avión. En Julio de 1967, durante una reunión de alto perfil entre ministros franceses, alemanes y británicos, se llegó a un acuerdo para una mayor cooperación entre las naciones europeas en el campo de la tecnología de la aviación, y para el desarrollo conjunto y la producción de un Airbus. La palabra airbus en este punto era un término genérico de aviación para un avión comercial más grande, y se consideraba aceptable en varios idiomas, incluido el francés.

Poco después de la reunión de Julio de 1967, el ingeniero francés Roger Béteille fue nombrado director técnico de lo que se convertiría en el programa A300, mientras que Henri Ziegler, jefe de operaciones de Sud Aviation, fue nombrado gerente general de la organización y el político alemán Franz Josef Strauss se convirtió en el presidente del consejo de supervisión. Roger Béteille elaboró un plan inicial de trabajo compartido para el proyecto, bajo el cual las empresas francesas producirían la cabina del avión, los sistemas de control y la parte central inferior del fuselaje, Hawker Siddeley fabricaría las alas, mientras que las compañías alemanas producirían la parte delantera, trasera y superior de las secciones centrales del fuselaje. El trabajo de adición incluyó elementos móviles de las alas que se producían en los Países Bajos, mientras que España producía el plano de cola horizontal.

Uno de los primeros objetivos de diseño para el A300 que Roger Béteille había subrayado la importancia era la incorporación de un alto nivel de tecnología, que serviría como una ventaja decisiva sobre los posibles competidores. Como tal, el A300 contaría con el primer uso de materiales compuestos de cualquier avión de pasajeros, los bordes delanteros y posteriores de la aleta de cola están compuestos de plástico reforzado con fibra de vidrio. Roger Béteille optó por el inglés como idioma de trabajo para el avión en desarrollo, así como en contra del uso de instrumentación y mediciones métricas, ya que la mayoría de las aerolíneas ya tenían aviones construidos en los Estados Unidos. Estas decisiones fueron parcialmente influenciadas por los comentarios de varias aerolíneas, como Air France y Lufthansa Gernam Airlines, ya que se había puesto énfasis en determinar los detalles de qué tipo de aviones buscaban los operadores potenciales. Según Airbus, este enfoque cultural de la investigación de mercado había sido crucial para el éxito a largo plazo de la compañía.

El 26 de Septiembre de 1967, los gobiernos británico, francés y de Alemania Occidental firmaron un Memorando de Entendimiento (MoU) para comenzar el desarrollo del Airbus A300 con capacidad para 300 asientos. En este punto, el A300 era solo el segundo programa de aviones conjunto más importante en Europa, el primero fue el Concorde anglo-francés. Según los términos del memorándum, Gran Bretaña y Francia recibirían cada uno una participación del 37,5 por ciento en el proyecto, mientras que Alemania recibió una participación del 25 por ciento. Sud Aviation fue reconocida como la compañía líder del A300, y Hawker Siddeley fue seleccionada como la compañía asociada británica. En ese momento, la noticia del anuncio se había visto empañada por el apoyo del Gobierno británico a Airbus, que coincidió con su negativa a respaldar al competidor propuesto por BAC, el BAC 2-11, a pesar de la preferencia por este último expresada por British European Airways (BEA). Otro parámetro fue el requisito de que Rolls-Royce desarrollara un nuevo motor para impulsar el avión propuesto; un derivado del Rolls-Royce RB211 en desarrollo, el RB207 de triple carrete, capaz de producir 47,500 lbf (211 kN). El costo del programa fue de US$ 4.6 mil millones de Dólares de 1993.

La sección circular del fuselaje de 5,64 m (222 pulgadas) de diámetro para asientos de 8 asientos y 2 contenedores LD3 debajo. Esto es parte del primer prototipo del A300, F-OCAZ, en exhibición en el Deutsches Museum de Munich.

En Diciembre de 1968, las compañías asociadas francesas y británicas (Sud Aviation y Hawker Siddeley) propusieron una configuración revisada, el Airbus A250 de 250 asientos. Se temía que la propuesta original de 300 asientos fuera demasiado grande para el mercado, por lo que se había reducido para producir el A250. Los cambios dimensionales involucrados en la contracción redujeron la longitud del fuselaje en 5,62 metros (18,4 pies) y el diámetro en 0,8 metros (31 pulgadas), reduciendo el peso total en 25 toneladas (55.000 libras). Para una mayor flexibilidad, el piso de la cabina se elevó para que los contenedores de carga LD3 estándar pudieran acomodarse uno al lado del otro, lo que permitió transportar más carga. Los refinamientos realizados por Hawker Siddeley al diseño del ala proporcionaron una mayor elevación y rendimiento general; Esto le dio a la aeronave la capacidad de subir más rápido y alcanzar una altitud de crucero nivelada antes que cualquier otro avión de pasajeros. Más tarde fue renombrado A300B.

Quizás el cambio más significativo del A300B fue que no requeriría el desarrollo de nuevos motores, siendo de un tamaño adecuado para ser impulsado por el RB211 de Rolls-Royce, o alternativamente los motores estadounidenses Pratt & Whitney JT9D y General Electric CF6; Se reconoció que este cambio reducía considerablemente los costos de desarrollo del proyecto. Para atraer clientes potenciales en el mercado estadounidense, se decidió que los motores General Electric CF6-50 impulsarían el A300 en lugar del RB207 británico; estos motores se producirían en cooperación con la firma francesa Snecma. Para entonces, Rolls-Royce había estado concentrando sus esfuerzos en desarrollar su motor turbofan RB211 y el progreso en el desarrollo del RB207 había sido lento durante algún tiempo, la empresa había sufrido debido a limitaciones de financiación, los cuales habían sido factores en la decisión de cambio de motor.

El 10 de Abril de 1969, unos meses después de que se anunciara la decisión de abandonar el RB207, el gobierno británico anunció que se retiraría de la empresa Airbus. En respuesta, Alemania Occidental propuso a Francia que estarían dispuestos a contribuir hasta el 50% de los costos del proyecto si Francia estaba dispuesta a hacer lo mismo. Además, el director general de Hawker Siddeley, Sir Arnold Alexander Hall, decidió que su compañía permanecería en el proyecto como un subcontratista favorito, desarrollando y fabricando las alas para el A300, que más tarde se convertiría en fundamental en el impresionante rendimiento de las versiones posteriores de vuelos nacionales cortos a intercontinentales largos. Hawker Siddeley gastó £ 35 millones de sus propios fondos, junto con un préstamo adicional de £ 35 millones del Gobierno de Alemania Occidental, en la máquina herramienta para diseñar y producir las alas.

Lanzamiento del Programa A300

El 29 de Mayo de 1969, durante el Salón Aeronáutico de París, el Ministro de Transporte francés Jean Chamant y el Ministro de Economía alemán Karl Schiller firmaron un acuerdo para lanzar oficialmente el Airbus A300, el primer avión bimotor de fuselaje ancho del mundo. La intención del proyecto era producir un avión que fuera más pequeño, más ligero y más económico que sus rivales estadounidenses de tres motores, el McDonnell Douglas DC-10 y el Lockheed L-1011 TriStar. Para satisfacer las demandas de Air France de un avión A300B de más de 250 asientos, se decidió estirar el fuselaje para crear una nueva variante, designada como A300B2, que se ofrecería junto con el A300B original de 250 asientos, en adelante denominado A300B1. El 3 de Septiembre de 1970, Air France firmó una carta de intención para seis A300, marcando el primer pedido que se ganó para el nuevo avión.

A raíz del acuerdo del Salón Aeronáutico de París, se decidió que, con el fin de proporcionar una gestión eficaz de las responsabilidades, se establecería un Groupement d’intérêt économique, permitiendo a los diversos socios trabajar juntos en el proyecto sin dejar de ser entidades comerciales separadas. El 18 de Diciembre de 1970, Airbus Industrie se estableció formalmente tras un acuerdo entre Aérospatiale (la recién fusionada Sud Aviation y Nord Aviation) de Francia y los antecedentes de Deutsche Aerospace de Alemania, cada uno recibiendo una participación del 50 por ciento en la compañía recién formada. En 1971, al consorcio se unió un tercer socio de pleno derecho, la firma española CASA, que recibió una participación del 4,2 por ciento, los otros dos miembros redujeron sus participaciones al 47,9 por ciento cada uno. En 1979, Gran Bretaña se unió al consorcio Airbus a través de British Aerospace, en el que Hawker Siddeley se había fusionado, que adquirió una participación del 20 por ciento en Airbus Industrie con Francia y Alemania reduciendo cada uno sus participaciones al 37,9 por ciento.

Prototipo y pruebas de vuelo

Airbus Industrie tuvo inicialmente su sede en París, que es donde se centraron las actividades de diseño, desarrollo, pruebas de vuelo, ventas, marketing y atención al cliente; la sede se trasladó a Toulouse en Enero de 1974. La línea de ensamblaje final para el A300 se ubicó adyacente al Aeropuerto Internacional de Toulouse Blagnac. El proceso de fabricación requirió el transporte de cada sección de avión producida por las empresas asociadas dispersas por toda Europa a esta ubicación. El uso combinado de transbordadores y carreteras se utilizó para el ensamblaje del primer A300, sin embargo, esto consumió mucho tiempo y Felix Kracht, director de producción de Airbus Industrie, no lo consideró ideal. La solución de Kracht fue que las diversas secciones del A300 fueran traídas a Toulouse por una flota de aviones Aero Spacelines Super Guppy derivados de Boeing 377, lo que significa que ninguno de los sitios de fabricación estaba a más de dos horas de distancia. Tener las secciones transportadas por aire de esta manera convirtió al A300 en el primer avión de pasajeros en utilizar técnicas de fabricación justo a tiempo, y permitió a cada compañía fabricar sus secciones como conjuntos totalmente equipados y listos para volar.

En Septiembre de 1969, comenzó la construcción del primer prototipo A300. El 28 de Septiembre de 1972, este primer prototipo fue presentado al público, realizó su primer vuelo desde el Aeropuerto Internacional de Toulouse-Blagnac el 28 de Octubre de ese año. Este vuelo inaugural, que se realizó un mes antes de lo previsto, duró una hora y 25 minutos; el capitán fue Max Fischl y el primer oficial fue Bernard Ziegler, hijo de Henri Ziegler. En 1972, el costo unitario fue de US$17,5 millones. El 5 de Febrero de 1973, el segundo prototipo realizó su primer vuelo. El programa de pruebas de vuelo, que involucró un total de cuatro aviones, estuvo relativamente libre de problemas, acumulando 1.580 horas de vuelo en todo momento. En Septiembre de 1973, como parte de los esfuerzos promocionales para el A300, el nuevo avión fue llevado en una gira de seis semanas por América del Norte y América del Sur, para demostrarlo a los ejecutivos de aerolíneas, pilotos y posibles clientes. Entre las consecuencias de esta expedición, supuestamente había llamado la atención del A300 sobre Frank Borman de Eastern Airlines, una de las cuatro grandes aerolíneas estadounidenses.

Entrada en servicio

El 15 de Marzo de 1974, las autoridades alemanas y francesas concedieron certificados de tipo para el A300, despejando el camino para su entrada en el servicio de ingresos. El 23 de Mayo de 1974, se recibió la certificación de la Administración Federal de Aviación (FAA). El primer modelo de producción, el A300B2, entró en servicio en 1974, seguido por el A300B4 un año después. Inicialmente, el éxito del consorcio fue pobre, en parte debido a las consecuencias económicas de la crisis del petróleo de 1973, pero en 1979 había 81 líneas de pasajeros A300 en servicio con 14 aerolíneas, junto con 133 pedidos en firme y 88 opciones. Diez años después del lanzamiento oficial del A300, la compañía había alcanzado una cuota de mercado del 26 por ciento en términos de valor en dólares, lo que permitió a Airbus Industries continuar con el desarrollo de su segundo avión, el Airbus A310.

Diseño

El A300 es un avión convencional de ala baja con dos turboventiladores sub-alares y una cola convencional. El Airbus A300 es un avión de pasajeros de fuselaje ancho de mediano a largo alcance; Tiene la distinción de ser el primer avión bimotor de fuselaje ancho del mundo. En 1977, el A300 se convirtió en el primer avión compatible con Extended Range Twin Operations (ETOPS), debido a sus altos estándares de rendimiento y seguridad. Otra primicia mundial del A300 es el uso de materiales compuestos en un avión comercial, que se utilizaron tanto en estructuras secundarias como en estructuras de fuselaje primarias posteriores, disminuyendo el peso total y mejorando la rentabilidad. Otras primicias incluyeron el uso pionero del control del centro de gravedad, logrado mediante la transferencia de combustible entre varias ubicaciones a través de la aeronave, y controles de vuelo secundarios con señales eléctricas.

El A300 está propulsado por un par de motores turbofan sub-alares, ya sea General Electric CF6 o Pratt & Whitney JT9D; El uso exclusivo de vainas de motor sub-alares permitió que cualquier motor turbofan adecuado se usara más fácilmente. La falta de un tercer motor montado en la cola, según la configuración trijet utilizada por algunos aviones competidores, permitió que las alas se ubicaran más adelante y redujeran el tamaño del estabilizador vertical y el elevador, lo que tuvo el efecto de aumentar el rendimiento de vuelo de la aeronave y la eficiencia del combustible.

Los socios de Airbus habían empleado la última tecnología, parte de la cual se derivaba del Concorde, en el A300. Según Airbus, las nuevas tecnologías adoptadas para el avión fueron seleccionadas principalmente para aumentar la seguridad, la capacidad operativa y la rentabilidad. Tras su entrada en servicio en 1974, el A300 era un avión muy avanzado, que influyó en los diseños posteriores de aviones de pasajeros. Los aspectos tecnológicos más destacados incluyen alas avanzadas de Havilland (más tarde BAE Systems) con secciones de perfil aerodinámico supercríticas para un rendimiento económico y superficies de control de vuelo avanzadas aerodinámicamente eficientes. La sección circular del fuselaje de 5,64 m (222 pulgadas) de diámetro permite un asiento de pasajeros de ocho asientos y es lo suficientemente ancha para 2 contenedores de carga LD3 uno al lado del otro. Las estructuras están hechas de palanquillas metálicas, lo que reduce el peso. Es el primer avión de pasajeros equipado con protección contra cizalladura del viento. Sus avanzados pilotos automáticos son capaces de volar la aeronave desde el ascenso hasta el aterrizaje, y tiene un sistema de frenado controlado eléctricamente.

Los A300 posteriores incorporaron otras características avanzadas, como la cabina de la tripulación orientada hacia adelante, que permitía a una tripulación de vuelo de dos pilotos volar el avión solo sin la necesidad de un ingeniero de vuelo, cuyas funciones estaban automatizadas; Este concepto de cabina de dos hombres fue una primicia mundial para un avión de fuselaje ancho. La instrumentación de vuelo de cabina de vidrio, que utilizaba monitores de tubo de rayos catódicos (CRT) para mostrar información de vuelo, navegación y advertencia, junto con pilotos automáticos duales totalmente digitales y computadoras digitales de control de vuelo para controlar los alerón, flaps y listones de vanguardia, también se adoptaron en modelos construidos más tarde. También se utilizaron compuestos adicionales, como el polímero reforzado con fibra de carbono (CFRP), así como su presencia en una proporción cada vez mayor de los componentes de la aeronave, incluidos los alerón, el timón, los frenos de aire y las puertas del tren de aterrizaje. Otra característica de los aviones posteriores fue la adición de vallas de punta de ala, que mejoraron el rendimiento aerodinámico y, por lo tanto, redujeron el consumo de combustible de crucero en aproximadamente un 1,5% para el A300-600.

Además de los deberes de los pasajeros, el A300 se convirtió en ampliamente utilizado por los operadores de carga aérea; según Airbus, es el avión de carga más vendido de todos los tiempos. Se construyeron varias variantes del A300 para satisfacer las demandas de los clientes, a menudo para diversos roles, como aviones cisterna de reabastecimiento aéreo, modelos de carga (nueva construcción y conversiones), aviones combinados, aviones de transporte militar y transporte VIP. Quizás la más visualmente única de las variantes es el A300-600ST Beluga, un modelo de carga de gran tamaño operado por Airbus para transportar secciones de aviones entre sus instalaciones de fabricación. El A300 fue la base y mantuvo un alto nivel de similitud con el segundo avión producido por Airbus, el Airbus A310 más pequeño.

Historia operacional

Air France introdujo el A300 el 23 de Mayo de 1974. El 23 de Mayo de 1974, el primer A300 en entrar en servicio realizó el primer vuelo comercial de este tipo, volando de París a Londres, para Air France. Inmediatamente después del lanzamiento, las ventas del A300 fueron débiles durante algunos años, y la mayoría de los pedidos fueron a aerolíneas que tenían la obligación de favorecer el producto de fabricación nacional, especialmente Air France y Lufthansa, las dos primeras aerolíneas en realizar pedidos para el tipo. Tras el nombramiento de Bernard Lathière como reemplazo de Henri Ziegler, se adoptó un enfoque de ventas agresivo. Indian Airlines fue la primera aerolínea nacional del mundo en comprar el A300, ordenando tres aviones con tres opciones. Sin embargo, entre Diciembre de 1975 y Mayo de 1977, no hubo ventas para el tipo. Durante este período, varios A300 de cola blanca, aviones completados pero no vendidos, se completaron y almacenaron en Toulouse, y la producción cayó a medio avión por mes en medio de llamadas para detener la producción por completo.

Korean Air, fue el primer cliente no europeo en Septiembre de 1974. Durante las pruebas de vuelo del A300B2, Airbus mantuvo una serie de conversaciones con Korean Air sobre el tema del desarrollo de una versión de mayor alcance del A300, que se convertiría en el A300B4. En Septiembre de 1974, Korean Air realizó un pedido de cuatro A300B4 (4) con opciones para dos (2) aviones adicionales; esta venta fue considerada significativa, pues fue la primera aerolínea internacional no europea en ordenar aviones Airbus. Airbus había visto el sudeste asiático como un mercado vital que estaba listo para abrirse y creía que Korean Air era la clave.

Las aerolíneas que operan el A300 en rutas de corta distancia se vieron obligadas a reducir las frecuencias para tratar de llenar el avión. Como resultado, perdieron pasajeros a manos de aerolíneas que operaban vuelos de fuselaje estrecho más frecuentes. Eventualmente, Airbus tuvo que construir su propio avión de fuselaje estrecho A320 para competir con el Boeing 737 y McDonnell Douglas DC-9/MD-80. El salvador del A300 fue el advenimiento de ETOPS, una regla revisada de la FAA que permite a los aviones bimotores volar rutas de larga distancia que antes estaban fuera de sus límites. Esto permitió a Airbus desarrollar el avión como un avión de mediano/largo alcance.

En 1977, la aerolínea estadounidense Eastern Air Lines arrendó cuatro A300 (4) como prueba en servicio. Frank Borman, ex astronauta y entonces CEO de la aerolínea, quedó impresionado de que el A300 consumiera un 30% menos de combustible, incluso menos de lo esperado, que su flota de L-1011. Borman procedió a ordenar veintitrés A300 (23), convirtiéndose en el primer cliente estadounidense para el tipo. Este orden se cita a menudo como el punto en el que Airbus llegó a ser visto como un serio competidor de los grandes fabricantes de aviones estadounidenses Boeing y McDonnell Douglas. El autor de aviación John Bowen alegó que varias concesiones, como garantías de préstamos de gobiernos europeos y pagos de compensación, también fueron un factor en la decisión. El avance de Eastern Air Lines fue seguido poco después por una orden de Pan Am. A partir de entonces, la familia A300 se vendió bien, llegando finalmente a un total de 561 aviones entregados.

En Diciembre de 1977, Aerocóndor Colombia se convirtió en el primer operador de Airbus en América Latina, arrendando un Airbus A300B4-2C, llamado Ciudad de Barranquilla.

A finales de la década de 1970, Airbus adoptó la llamada estrategia de la «Ruta de la Seda», dirigida a las aerolíneas del Lejano Oriente. Como resultado, el avión encontró un favor particular con las aerolíneas asiáticas, siendo comprado por Japan Air System, Korean Air, China Eastern Airlines, Thai Airways International, Singapore Airlines, Malaysia Airlines, Philippine Airlines, Garuda Indonesia, China Airlines, Pakistan International Airlines, Indian Airlines, Trans Australia Airlines y muchos otros. Como Asia no tenía restricciones similares a la regla de sesenta minutos de la FAA para aviones bimotores que existía en ese momento, las aerolíneas asiáticas utilizaron A300 para rutas a través de la Bahía de Bengala y el Mar del Sur de China.

En 1977, el A300B4 se convirtió en el primer avión compatible con ETOPS, calificando para Operaciones Bimotor Extendidas sobre el agua, proporcionando a los operadores más versatilidad en el enrutamiento. En 1982 Garuda Indonesia Airlines se convirtió en la primera aerolínea en volar el A300B4-200FF. En 1981, Airbus estaba creciendo rápidamente, con más de 400 aviones vendidos a más de cuarenta aerolíneas.

En 1989, el operador chino China Eastern Airlines recibió su primer A300; en 2006, la aerolínea operaba alrededor de dieciocho A300 (18), lo que la convierte en el mayor operador tanto del A300 como del A310 en ese momento. El 31 de Mayo de 2014, China Easternr Airlilnes retiró oficialmente el último A300-600 de su flota, después de haber comenzado a retirar el tipo en 2010. De 1997 a 2014, un solo A300, designado A300 Zero-G, fue operado por la Agencia Espacial Europea (ESA), el Centre national d’études spatiales (CNES) y el Centro Aeroespacial Alemán (DLR) como un avión de gravedad reducida para realizar investigaciones sobre microgravedad; el A300 es el avión más grande que se haya utilizado en esta capacidad. Un vuelo típico duraría dos horas y media, lo que permitiría realizar hasta 30 parábolas por vuelo.

El 12 de Julio de 2007, el último A300, un carguero, fue entregado a FedEx Express, a partir de Mayo de 2022 el mayor operador con 65 aviones aún en servicio. En la década de 1990, el A300 estaba siendo fuertemente promocionado como un carguero de carga. El mayor operador de carga del A300 es FedEx Express, que tiene 65 aviones A300 en servicio a partir de Mayo de 2022. UPS Airlines también opera 52 versiones de carga del A300.

La versión final fue el A300-600R y está clasificado para ETOPS de 180 minutos. El A300 ha disfrutado de un renovado interés en el mercado de segunda mano para la conversión a cargueros; grandes números se estaban convirtiendo a fines de la década de 1990. Las versiones de carga, ya sean A300-600 de nueva construcción o A300-600, A300B2 y B4 de pasajeros convertidos, representan la mayor parte de la flota mundial de cargueros después del carguero Boeing 747.

El A300 proporcionó a Airbus la experiencia de fabricar y vender aviones de manera competitiva. El fuselaje básico del A300 fue posteriormente estirado (A330 y A340), acortado (A310), o modificado en derivados (A300-600ST Beluga Super Transporter). En 2006, el costo unitario de un -600F fue de US$ 105 millones. En marzo de 2006, Airbus anunció el cierre inminente de la línea de ensamblaje final del A300/A310, convirtiéndolos en el primer avión Airbus en ser descontinuado. El A300 de producción final, un carguero A300F, realizó su vuelo inicial el 18 de Abril de 2007, y fue entregado a FedEx Express el 12 de Julio de 2007. Airbus ha anunciado un paquete de apoyo para mantener los A300 volando comercialmente. Airbus ofrece el carguero A330-200F como reemplazo de las variantes de carga del A300.

La vida útil de la flota de UPS de 52 A300, entregados de 2000 a 2006, se extenderá hasta 2035 con una actualización de la cabina de vuelo basada en la aviónica Honeywell Primus Epic; nuevas pantallas y sistema de gestión de vuelo (FMS), radar meteorológico mejorado, un sistema de mantenimiento central y una nueva versión del actual sistema mejorado de advertencia de proximidad al suelo. Con un uso ligero de solo dos o tres ciclos por día, no alcanzará el número máximo de ciclos para entonces. La primera modificación se realizará en Airbus Toulouse en 2019 y se certificará en 2020. A partir de Julio de 2017, hay 211 A300 en servicio con 22 operadores, siendo el operador más grande FedEx Express con 68 aviones A300-600F.

Variantes del Airbus A300

A300B1

Los dos prototipos A300B1 tenían 51 m (167 pies) de largo. El A300B1 fue la primera variante en despegar. Tenía un peso máximo de despegue (MTOW) de 132 t (291,000 lb), tenía 51 m (167 pies) de largo y estaba propulsado por dos motores General Electric CF6-50A. Solo se construyeron dos prototipos de la variante antes de que se adaptara al A300B2, la primera variante de producción del avión. El segundo prototipo fue arrendado a Trans European Airways en 1974.

A300B2

El A300B2 tenía 53,6 m (176 pies) de largo, 2,6 m (8,5 pies) más largo que el A300B1.

A300B2-100

Respondiendo a la necesidad de más asientos de Air France, Airbus decidió que la primera variante de producción debería ser más grande que el prototipo original A300B1. El A300B2-100 con motor CF6-50A era 2,6 m (8,5 pies) más largo que el A300B1 y tenía un MTOW aumentado de 137 t (302,000 lb), lo que permitía 30 asientos adicionales y elevaba el número típico de pasajeros a 281, con capacidad para 20 contenedores LD3. Se construyeron dos prototipos y la variante realizó su primer vuelo el 28 de Junio de 1973, se certificó el 15 de Marzo de 1974 y entró en servicio con Air France el 23 de Mayo de 1974.

A300B2-200

Para el A300B2-200, originalmente designado como A300B2K, se introdujeron aletas Krueger en la raíz del borde de ataque, los ángulos de lamas se redujeron de 20 grados a 16 grados, y se realizaron otros cambios relacionados con la elevación para introducir un sistema de elevación alta. Esto se hizo para mejorar el rendimiento cuando se opera en aeropuertos de gran altitud, donde el aire es menos denso y la generación de elevación se reduce. La variante tenía un aumento de MTOW de 142t (313,000 lb) y estaba propulsada por motores CF6-50C, fue certificada el 23 de Junio de 1976 y entró en servicio con South African Airways en Noviembre de 1976. Los modelos CF6-50C1 y CF6-50C2 también se instalaron más tarde dependiendo de los requisitos del cliente, estos se certificaron el 22 de Febrero de 1978 y el 21 de Febrero de 1980 respectivamente.

A300B2-320

El A300B2-320 introdujo el motor Pratt & Whitney JT9D y fue propulsado por motores JT9D-59A. Retuvo el MTOW de 142 t (313,000 lb) del B2-200, fue certificado el 4 de Enero de 1980 y entró en servicio con Scandinavian Airlines el 18 de Febrero de 1980, con solo cuatro producidos. El total de las variantes producidas de la familia A300 corresponden a: A300B2-100 32 unidades, A300B2-200 25 unidades, A300B2-320 4 unidades.

A300B4

El A300B4-100 despegó por primera vez el 26 de Diciembre de 1974, mantuvo la longitud del B2 pero presentó una mayor capacidad de combustible.

A300B4-100

La variante inicial del A300B4, más tarde llamada A300B4-100, incluía un tanque de combustible central para una mayor capacidad de combustible de 47.5 toneladas (105,000 lb), y tenía un MTOW aumentado de 157.5 toneladas (347,000 lb). También presentaba aletas Krueger y tenía un sistema de elevación alta similar al que más tarde se instaló en el A300B2-200. La variante realizó su primer vuelo el 26 de Diciembre de 1974, fue certificada el 26 de Marzo de 1975 y entró en servicio con Germanair en Mayo de 1975.

A300B4-200

El A300B4-200 tenía un MTOW aumentado de 165 toneladas (364,000 lb) y presentaba un tanque de combustible opcional adicional en la bodega de carga trasera, lo que reduciría la capacidad de carga en dos contenedores LD3. La variante fue certificada el 26 de Abril de 1979. Lavariante B4 ha sido producida en dos versiones: A300B4-100 con 47 unidades, A300B4-200 con 136 unidades.

A300-600

Con pequeñas vallas de punta de ala, el A300-600 entró en servicio en Junio de 1984 con Saudi Arabian Airlines. El A300-600, oficialmente designado como A300B4-600, era ligeramente más largo que las variantes A300B2 y A300B4 y tenía un mayor espacio interior al usar un fuselaje trasero similar al Airbus A310, esto le permitió tener dos filas adicionales de asientos. Inicialmente fue propulsado por motores Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7R4H1, pero más tarde fue equipado con motores General Electric CF6-80C2, con motores Pratt & Whitney PW4056 o PW4058 que se introdujeron en 1986. Otros cambios incluyen un ala mejorada con un borde de fuga recamberado, la incorporación de aletas Fowler de una sola ranura más simples, la eliminación de las cercas de listones y la eliminación de los alerones fuera de borda después de que se consideraron innecesarios en el A310. La variante realizó su primer vuelo el 8 de Julio de 1983, fue certificada el 9 de Marzo de 1984 y entró en servicio en Junio de 1984 con Saudi Arabian Airlines. Se han vendido un total de 313 A300-600 (todas las versiones). El A300-600 tiene una cabina similar a la del A310, utilizando tecnología digital y pantallas electrónicas, eliminando la necesidad de un ingeniero de vuelo. La FAA emite una única habilitación de tipo que permite la operación tanto del A310 como del A300-600.

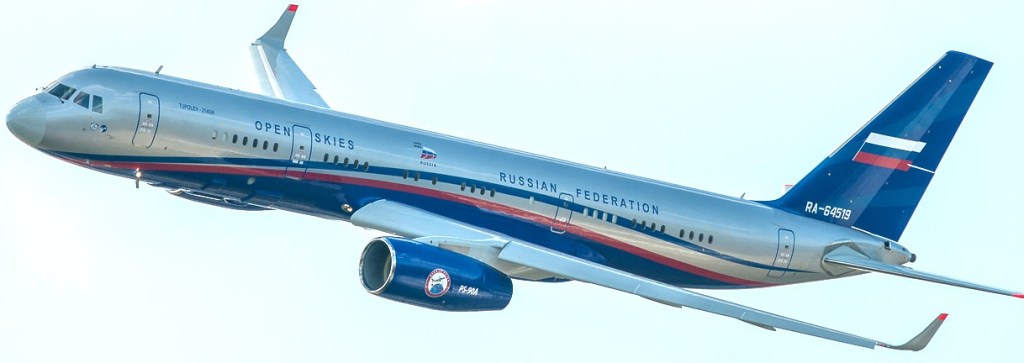

El A300-600 ha tenido la designación oficial como A300B4-600. El modelo de referencia de la Serie 600. El A300-620C como designación oficial A300C4-620, una versión de carguero convertible que han sido entregados cuatro unidades entre 1984 y 1985. A300-600F como designación oficial: A300F4-600, la versión de carga de la línea de base de la Serie 600. El A300-600R como designación oficial: A300B4-600R con rango aumentado de la Serie 600, logrado con un tanque de combustible de ajuste adicional en la cola. La primera entrega en 1988 a American Airlines; todos los A300 construidos desde 1989 (cargueros incluidos) son Seerie 600R. Japan Air System, más tarde fusionada con Japan Airlines, recibió el último A300 de pasajeros de nueva construcción, un A300-622R, en Noviembre de 2002. El A300-600RC con designación oficial A300C4-600R, la versión de carga convertible del 600R, con una entrega de dos unidades en 1999. El A300-600RF con designación oficial A300F4-600R, la versión carguero del 600R. Todos los A300 entregados entre Noviembre de 2002 y el 12 de Julio de 2007 (última entrega del A300) fueron A300-600RF.

A300B10 / A310

Airbus tenía demanda de un avión más pequeño que el A300 como complemento. El 7 de Julio de 1978, el A310, inicialmente denominado como A300B10 fue lanzado con órdenes de Swissair y Lufthansa German Airlines. El 3 de Abril de 1982, el primer prototipo realizó su primer vuelo y recibió su certificación de tipo el 11 de Marzo de 1983. Manteniendo la misma sección transversal de ocho puntos, el A310 es 6,95 m (22,8 pies) más corto que las variantes iniciales del A300, y tiene un ala más pequeña de 219 m 2 (2.360 pies cuadrados), por debajo de los 260 m 2 (2.800 pies cuadrados). El A310 introdujo una cabina de cristal de dos tripulantes, más tarde adoptada para el A300-600 con una clasificación de tipo común. Estaba propulsado por los mismos turbofans GE CF6-80 o Pratt & Whitney JT9D que PW4000. Tiene capacidad para 220 pasajeros en dos clases, o 240 en todas las clases económicas, y puede volar hasta 5.150 nmi (9.540 km). Tiene salidas de ala entre los dos pares de puertas delanteras y traseras principales. En Abril de 1983, el avión entró en servicio de ingresos con Swissair y compitió con el Boeing 767-200, introducido seis meses antes. Su mayor alcance y las regulaciones ETOPS le permitieron ser operado en vuelos transatlánticos. Hasta la última entrega en junio de 1998, se produjeron 255 aviones, ya que fue sucedido por el Airbus A330-200 más grande. Tiene versiones de aviones de carga, y se derivó en el Airbus A310 MRTT cisterna / transporte militar.

A300-600ST

El Airbus Beluga se basa en el A300 con una bodega de carga de gran tamaño en la parte superior. Comúnmente conocido como Airbus Beluga o Airbus Super Transporter, estos cinco fuselajes son utilizados por Airbus para transportar piezas entre las instalaciones de fabricación dispares de la compañía, lo que permite la distribución de trabajo compartido. Reemplazaron a los cuatro Aero Spacelines Super Guppys utilizados anteriormente por Airbus.

A300, precursor de Airbus

A partir de Junio de 2022, había 229 aviones de la familia A300 en servicio comercial. Los cinco operadores más grandes fueron FedEx Express (70), UPS Airlines (52), European Air Transport Leipzig (22), Mahan Air (13) e Iran Air (11).

La línea A300 ha sido la primer aeronave comercial widebody con el caracter de competir con las principales compañías industriales del mundo permitiendo cortar con la hegemonía de la industria de la avación comercial. Airbus ha logrado conquistar los cielos por primera vez en Octubre de 1972, un proyecto que había nacido bajo un enorme escepticismo, alcanzando la supremacía aérea gracias a su modelo A300, hace cincuenta años atrás de su primer vuelo. ![]()

Ξ 50th anniversaries Airbus A300 Ξ

Airbus launched its first large aircraft

![]()

The first wide-body twin-engine in the world took a leap half a century ago by the aircraft manufacturer Airbus Industrie, spearheading the end of the US monopoly in commercial aviation. On October 28, 1972, the Airbus A300 made its inaugural flight, the beginning of the true European industry that broke the Boeing-McDonnell Douglas duopoly.

The Airbus A300 is a wide-body aircraft developed and manufactured by Airbus. In September 1967, aircraft manufacturers in the United Kingdom, France, and West Germany signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to develop a large passenger aircraft. West Germany and France reached an agreement on May 29, 1969 after the British withdrew from the project on April 10, 1969. The European collaborative aerospace manufacturer Airbus Industrie was formally created on December 18, 1970 to develop and produce it. The prototype first flew on October 28, 1972.

The first twin-engine wide-body aircraft, the A300 normally seats 247 passengers in two classes at a range of 5,375 to 7,500 km (2,900 to 4,050 nmi). Initial variants are powered by General Electric CF6-50 or Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofans and have a three-crew flight deck. The upgraded A300-600 has a two-crew cabin and upgraded CF6-80C2 or PW4000 engines; it made its first flight on July 8, 1983 and entered service later that year. The A300 is the basis of the smaller A310 (it first flew in 1982) and was adapted into a freighter version. Its cross section was retained for the larger four-engined A340 (1991) and the larger twin-engined A330 (1992). It is also the base for the large Beluga transport (1994).

Launch customer Air France introduced the type on 23 May 1974. After initially limited demand, sales took off as the type proved itself in early service, beginning three decades of steady orders. It is similar in capacity to the Boeing 767-300, introduced in 1986, but lacked the 767-300ER range. During the 1990s, the A300 became popular with cargo aircraft operators, both as airliner conversions and as original builds. Production ceased in July 2007 after 561 deliveries. As of June 2022, there were 229 A300 Family aircraft in commercial service.

In 1966, Hawker Siddeley, Nord Aviation and Breguet Aviation proposed the 260-seat wide-body HBN 100 in a similar configuration. During the 1960s, European aircraft manufacturers such as UK-based Hawker Siddeley and British Aircraft Corporation and France’s Sud Aviation had ambitions to build a new 200-seat airliner for the growing airline market. civil Aviation. While studies were undertaken and considered, such as a stretched twin-engine variant of the Hawker Siddeley Trident and an expanded development of the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) One-Eleven, designated BAC Two-Eleven, it was recognized that if each of the European manufacturers launched aircraft similar to the market at the same time, none would reach the sales volume necessary to make them viable. In 1965, a British Government study, known as the Plowden Report, had found that British aircraft production costs were between 10% and 20% higher than their American counterparts due to shorter production runs, which which was due in part to the fractured European market. To overcome this factor, the report recommended the search for multinational collaboration projects between the main aircraft manufacturers in the region.

European manufacturers were willing to explore possible programs; the proposed 260-seat wide-body HBN 100 between Hawker Siddeley, Nord Aviation and Breguet Aviation is one example. National governments were also willing to support such efforts amid the belief that US manufacturers could dominate the European Economic Community; in particular, Germany had ambitions for a multinational aircraft project to invigorate its aircraft industry, which had declined considerably after World War II. By the mid-1960s, both Air France and American Airlines had expressed interest in a short-haul twin-engined wide-body aircraft, indicating a market demand for such an aircraft to be produced. In July 1967, during a high-profile meeting between French, German, and British ministers, an agreement was reached for greater cooperation among European nations in the field of aviation technology, and for the joint development and production of an Airbus. The word airbus at this point was a generic aviation term for a larger commercial airliner, and was considered acceptable in a number of languages, including French.

Shortly after the July 1967 meeting, French engineer Roger Béteille was appointed technical director of what would become the A300 program, while Henri Ziegler, head of operations at Sud Aviation, was appointed general manager of the organization and the German politician Franz Josef Strauss became the chairman of the supervisory board. Roger Béteille drew up an initial work-sharing plan for the project, under which French companies would produce the aircraft’s cockpit, control systems and lower center fuselage, Hawker Siddeley would manufacture the wings, while German companies would produce the front, rear and top of the center sections of the fuselage. Addition work included movable wing elements that were produced in the Netherlands, while Spain produced the horizontal tailplane.

One of the early design goals for the A300 that Roger Béteille had stressed as important was the incorporation of a high level of technology, which would serve as a decisive advantage over would-be competitors. As such, the A300 would feature the first use of composite materials of any airliner, the leading and trailing edges of the tail fin being made of fiberglass reinforced plastic. Roger Béteille opted for English as the working language for the aircraft under development, as well as against the use of metric instrumentation and measurements, as most airlines already had aircraft built in the United States. These decisions were partially influenced by feedback from various airlines, such as Air France and Lufthansa Gernam Airlines, as emphasis had been placed on determining the specifics of what type of aircraft potential operators were looking for. According to Airbus, this cultural approach to market research had been crucial to the company’s long-term success.

On September 26, 1967, the British, French and West German governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to begin development of the 300-seat Airbus A300. At this point, the A300 was only the second largest joint aircraft program in Europe, the first being the Anglo-French Concorde. Under the terms of the memorandum, Britain and France would each receive a 37.5 percent stake in the project, while Germany received a 25 percent stake. Sud Aviation was recognized as the leading company for the A300, and Hawker Siddeley was selected as the British partner company. At the time, news of the announcement had been clouded by the British Government’s support for Airbus, which coincided with its refusal to back BAC’s proposed competitor, the BAC 2-11, despite the preference for the latter expressed by British European Airways (BEA). Another parameter was the requirement that Rolls-Royce develop a new engine to power the proposed aircraft; a derivative of the Rolls-Royce RB211 under development, the triple-spool RB207, capable of producing 47,500 lbf (211 kN). The cost of the program was US$4.6 billion in 1993 dollars.

The 5.64 m (222 in) diameter circular fuselage section for 8-seat seating and 2 LD3 containers below. This is part of the first A300 prototype, F-OCAZ, on display at the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

In December 1968, the associated French and British companies (Sud Aviation and Hawker Siddeley) proposed a revised configuration, the 250-seat Airbus A250. It was feared that the original 300-seat proposal was too big for the market, so it had been scaled back to produce the A250. The dimensional changes involved in shrinkage reduced the fuselage length by 5.62 meters (18.4 ft) and the diameter by 0.8 meters (31 in), reducing the overall weight by 25 tons (55,000 lb). For added flexibility, the cabin floor was raised so that standard LD3 cargo containers could be accommodated side by side, allowing more cargo to be carried. Refinements made by Hawker Siddeley to the wing design provided increased lift and overall performance; This gave the aircraft the ability to climb faster and reach a level cruising altitude sooner than any other airliner. It was later renamed A300B.

Perhaps the most significant change to the A300B was that it would not require new engine development, being sized to be powered by the Rolls-Royce RB211, or alternatively the American Pratt & Whitney JT9D and General Electric CF6 engines; This change was recognized as significantly reducing project development costs. To attract potential customers in the US market, it was decided that General Electric CF6-50 engines would power the A300 instead of the British RB207; these engines would be produced in cooperation with the French firm Snecma. By this time, Rolls-Royce had been concentrating its efforts on developing its RB211 turbofan engine and progress on the RB207 development had been slow for some time, the company having suffered due to funding constraints, both of which had been factors in the decision. engine change.

On April 10, 1969, a few months after the decision to abandon the RB207 was announced, the British government announced that it would withdraw from the Airbus company. In response, West Germany proposed to France that they would be willing to contribute up to 50% of the project costs if France was willing to do the same. In addition, Hawker Siddeley CEO Sir Arnold Alexander Hall decided that his company would remain on the project as a favored subcontractor, developing and manufacturing the wings for the A300, which would later become instrumental in the versions’ impressive performance. from short domestic flights to long intercontinental ones. Hawker Siddeley spent £35 million of its own funds, along with a further £35 million loan from the West German Government, on the machine tool to design and produce the wings.

Launch of the A300 Program

On May 29, 1969, during the Paris Air Show, French Transport Minister Jean Chamant and German Economy Minister Karl Schiller signed an agreement to officially launch the Airbus A300, the world’s first twin-engine wide-body aircraft. The intent of the project was to produce an aircraft that was smaller, lighter, and more economical than its American three-engine rivals, the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar. To meet Air France’s demands for an A300B aircraft with more than 250 seats, it was decided to stretch the fuselage to create a new variant, designated the A300B2, to be offered alongside the original 250-seat A300B, hereafter referred to as the A300B1. On September 3, 1970, Air France signed a letter of intent for six A300s, marking the first order won for the new aircraft.

Following the Paris Air Show agreement, it was decided that, in order to provide effective management of responsibilities, a Groupement d’intérêt économique would be established, allowing the various partners to work together on the project while remaining entities separate commercials. On December 18, 1970, Airbus Industrie was formally established following an agreement between Aérospatiale (the newly merged Sud Aviation and Nord Aviation) of France and Deutsche Aerospace antecedents of Germany, each receiving a 50 percent stake in the company. newly formed. In 1971, the consortium was joined by a third full partner, the Spanish firm CASA, which received a 4.2 percent share, the other two members reducing their holdings to 47.9 percent each. In 1979, Britain joined the Airbus consortium through British Aerospace, into which Hawker Siddeley had merged, which took a 20 per cent stake in Airbus Industrie with France and Germany each reducing their holdings to 37.9 per cent. hundred.

Prototype and flight tests

Airbus Industrie was initially headquartered in Paris, which is where design, development, flight testing, sales, marketing and customer support activities were focused; headquarters moved to Toulouse in January 1974. The final assembly line for the A300 was located adjacent to Toulouse Blagnac International Airport. The manufacturing process required the transportation of every aircraft section produced by the associated companies scattered throughout Europe to this location. The combined use of ferries and roads was used for the assembly of the first A300, however this was time consuming and was not considered ideal by Felix Kracht, Director of Production at Airbus Industrie. Kracht’s solution was for the various sections of the A300 to be brought to Toulouse by a fleet of Boeing 377-derived Aero Spacelines Super Guppy aircraft, meaning none of the manufacturing sites were more than two hours away. Having the sections airlifted in this way made the A300 the first airliner to use just-in-time manufacturing techniques, and allowed each company to manufacture their sections as fully equipped, ready-to-fly assemblies.

In September 1969, construction of the first A300 prototype began. On September 28, 1972, this first prototype was presented to the public, it made its first flight from the Toulouse-Blagnac International Airport on October 28 of that year. This inaugural flight, which took place a month ahead of schedule, lasted one hour and 25 minutes; the captain was Max Fischl and the first officer was Bernard Ziegler, son of Henri Ziegler. In 1972, the unit cost was US$17.5 million. On February 5, 1973, the second prototype made its first flight. The flight test programme, involving a total of four aircraft, was relatively trouble-free, racking up 1,580 flight hours throughout. In September 1973, as part of the promotional efforts for the A300, the new aircraft was taken on a six-week tour of North and South America to demonstrate it to airline executives, pilots and prospective customers. Among the fallout from this expedition, he had allegedly drawn the A300’s attention to Frank Borman of Eastern Airlines, one of the Big Four American airlines.

FIRST AIR FRANCE AIRBUS A300 FLIGHT 05/23/1974 PARIS—LONDON

Entry into service

On March 15, 1974, the German and French authorities granted type certificates for the A300, clearing the way for its entry into revenue service. On May 23, 1974, certification was received from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The first production model, the A300B2, entered service in 1974, followed by the A300B4 a year later. Initially the consortium’s success was poor, partly due to the economic fallout from the 1973 oil crisis, but by 1979 there were 81 A300 passenger lines in service with 14 airlines, along with 133 firm orders and 88 options. Ten years after the official launch of the A300, the company had achieved a 26 percent market share in dollar value terms, allowing Airbus Industries to continue development of its second aircraft, the Airbus A310.

Design

The A300 is a conventional low-wing aircraft with two underwing turbofans and a conventional tail. The Airbus A300 is a medium to long-range wide-body airliner; It has the distinction of being the world’s first wide-body twin-engine aircraft. In 1977, the A300 became the first Extended Range Twin Operations (ETOPS) compliant aircraft, due to its high performance and safety standards. Another world first for the A300 is the use of composite materials in a commercial aircraft, which were used in both secondary structures and primary rear fuselage structures, lowering overall weight and improving cost efficiency. Other firsts included the pioneering use of center of gravity control, achieved by transferring fuel between various locations throughout the aircraft, and secondary flight controls with electrical signals.

The A300 is powered by a pair of underwing turbofan engines, either General Electric CF6 or Pratt & Whitney JT9D; Exclusive use of underwing engine pods allowed any suitable turbofan engine to be used more easily. The lack of a tail-mounted third engine, as per the trijet configuration used by some competing aircraft, allowed the wings to be located further forward and reduced the size of the vertical stabilizer and elevator, which had the effect of increasing the performance of aircraft flight and fuel efficiency.

Airbus partners had employed the latest technology, some of which was derived from the Concorde, in the A300. According to Airbus, the new technologies adopted for the aircraft were selected primarily to increase safety, operational capacity and profitability. Upon entering service in 1974, the A300 was a highly advanced aircraft, influencing subsequent airliner designs. Technological highlights include advanced de Havilland (later BAE Systems) wings with supercritical airfoil sections for economical performance and advanced aerodynamically efficient flight control surfaces. The 5.64 m (222 in) diameter circular fuselage section allows for eight-seat passenger seating and is wide enough for 2 LD3 cargo containers side by side. The structures are made of metal billets, which reduces weight. It is the first passenger aircraft equipped with wind shear protection. Its advanced autopilots are capable of flying the aircraft from climb to landing, and it has an electrically controlled braking system.

Later A300s incorporated other advanced features, such as the forward-facing crew cabin, which allowed a two-pilot flight crew to fly the aircraft alone without the need for a flight engineer, whose duties were automated; This two-man cockpit concept was a world first for a wide-body aircraft. The glass cockpit flight instrumentation, which used cathode ray tube (CRT) monitors to display flight, navigation and warning information, along with dual all-digital autopilots and digital flight control computers to control the aileron, flaps and cutting-edge slats, were also adopted in models built later. Additional composites such as carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) were also used, as well as their presence in an increasing proportion of aircraft components, including ailerons, rudders, air brakes and aircraft doors. undercarriage. Another feature on later aircraft was the addition of wingtip fencing, which improved aerodynamic performance and thus reduced cruise fuel consumption by approximately 1.5% for the A300-600.

In addition to passenger duties, the A300 became widely used by air cargo operators; according to Airbus, it is the best-selling cargo plane of all time. Various variants of the A300 were built to meet customer demands, often for various roles such as aerial refueling tankers, cargo models (new build and conversions), combination aircraft, military transport aircraft and VIP transport. Perhaps the most visually unique of the variants is the A300-600ST Beluga, an oversized cargo model operated by Airbus to transport aircraft sections between its manufacturing facilities. The A300 was the basis for and maintained a high level of similarity to the second aircraft produced by Airbus, the smaller Airbus A310.

Operational history

Air France introduced the A300 on May 23, 1974. On May 23, 1974, the first A300 to enter service made the first commercial flight of its kind, flying from Paris to London, for Air France. Immediately after launch, sales of the A300 were weak for a few years, with most orders going to airlines that had an obligation to favor the domestically-built product, especially Air France and Lufthansa, the first two airlines to place orders for the type. Following the appointment of Bernard Lathière as Henri Ziegler’s replacement, an aggressive sales approach was taken. Indian Airlines was the first national carrier in the world to purchase the A300, ordering three aircraft with three options. However, between December 1975 and May 1977, there were no sales for the type. During this period, a number of white-tailed A300s, aircraft completed but not sold, were completed and stored in Toulouse, with production falling to half an aircraft per month amid calls to stop production altogether.

Korean Air was the first non-European customer in September 1974. During flight testing of the A300B2, Airbus had a series of discussions with Korean Air on the subject of developing a longer range version of the A300, which would become the A300B4. In September 1974, Korean Air placed an order for four (4) A300B4s with options for two (2) additional aircraft; this sale was considered significant, as it was the first non-European international airline to order Airbus aircraft. Airbus had seen Southeast Asia as a vital market ready to open up and believed that Korean Air was the key.

Airlines operating the A300 on short-haul routes were forced to cut frequencies to try to fill the plane. As a result, they lost passengers to airlines operating more frequent narrow-body flights. Eventually, Airbus had to build its own A320 narrow-body airliner to compete with the Boeing 737 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9/MD-80. The A300’s savior was the advent of ETOPS, a revised FAA rule that allows twin-engine aircraft to fly long-haul routes that were previously off limits. This allowed Airbus to develop the aircraft as a medium/long range aircraft.

In 1977, the US airline Eastern Air Lines leased four A300s (4) as a trial in service. Frank Borman, a former astronaut and then CEO of the airline, was impressed that the A300 burned 30% less fuel, even less than expected, than his fleet of L-1011s. Borman proceeded to order twenty-three A300s (23), becoming the first American customer for the type. This order is often cited as the point at which Airbus came to be seen as a serious competitor to the large American aircraft manufacturers Boeing and McDonnell Douglas. Aviation author John Bowen alleged that various concessions, such as loan guarantees from European governments and compensation payments, were also a factor in the decision. Eastern Air Lines’ advance was followed shortly thereafter by an order from Pan Am. Thereafter the A300 family sold well, eventually reaching a total of 561 aircraft delivered.

In December 1977, Aerocóndor Colombia became the first Airbus operator in Latin America, leasing an Airbus A300B4-2C, named Ciudad de Barranquilla.

In the late 1970s, Airbus adopted the so-called «Silk Road» strategy, targeting airlines in the Far East. As a result, the aircraft found particular favor with Asian airlines, being bought by Japan Air System, Korean Air, China Eastern Airlines, Thai Airways International, Singapore Airlines, Malaysia Airlines, Philippine Airlines, Garuda Indonesia, China Airlines, Pakistan International Airlines. Indian Airlines, Trans Australia Airlines and many others. As Asia did not have restrictions similar to the FAA’s sixty-minute rule for twin-engine aircraft that existed at the time, Asian airlines used A300s for routes through the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea.

In 1977, the A300B4 became the first ETOPS-compliant aircraft, qualifying for Extended Twin-Engine Operations over water, providing operators with more versatility in routing. In 1982 Garuda Indonesia Airlines became the first airline to fly the A300B4-200FF. By 1981, Airbus was growing rapidly, with more than 400 aircraft sold to more than forty airlines.

In 1989, Chinese carrier China Eastern Airlines took delivery of its first A300; in 2006 the airline operated around eighteen A300s (18), making it the largest operator of both the A300 and A310 at the time. On May 31, 2014, China Eastern Airlines officially retired the last A300-600 from its fleet, having begun retiring the type in 2010. From 1997 to 2014, a single A300, designated A300 Zero-G, was operated by the European Space Agency (ESA), the Center national d’études spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) as a low-gravity aircraft for microgravity research; the A300 is the largest aircraft ever used in this capacity. A typical flight would take two and a half hours, allowing up to 30 parabolas per flight.

On July 12, 2007, the last A300, a freighter, was delivered to FedEx Express, as of May 2022 the largest operator with 65 aircraft still in service. In the 1990s the A300 was being heavily promoted as a cargo freighter. The largest freighter operator of the A300 is FedEx Express, which has 65 A300 aircraft in service as of May 2022. UPS Airlines also operates 52 freighter versions of the A300.

The final version was the A300-600R and is rated for 180 minute ETOPS. The A300 has enjoyed renewed interest on the second-hand market for conversion to freighters; large numbers were being converted by the late 1990s. Freighter versions, whether newly built A300-600s or converted passenger A300-600s, A300B2s and B4s, account for the majority of the world’s freighter fleet after the Boeing 747 freighter.

The A300 provided Airbus with the experience to build and sell aircraft competitively. The basic A300 fuselage was later stretched (A330 and A340), shortened (A310), or modified into derivatives (A300-600ST Beluga Super Transporter). In 2006, the unit cost of a -600F was US$105 million. In March 2006, Airbus announced the imminent closure of the A300/A310 final assembly line, making them the first Airbus aircraft to be discontinued. The final production A300, an A300F freighter, made its maiden flight on April 18, 2007, and was delivered to FedEx Express on July 12, 2007. Airbus has announced a support package to keep the A300 flying commercially. Airbus offers the A330-200F freighter as a replacement for freighter variants of the A300.

The service life of UPS’s fleet of 52 A300s, delivered from 2000 to 2006, will be extended to 2035 with a flight deck upgrade based on Honeywell Primus Epic avionics; new displays and flight management system (FMS), improved weather radar, a central maintenance system, and a new version of the current improved ground proximity warning system. With light use of only two or three cycles per day, you will not reach the maximum number of cycles by then. The first modification will take place at Airbus Toulouse in 2019 and it will be certified in 2020. As of July 2017, there are 211 A300s in service with 22 operators, the largest operator being FedEx Express with 68 A300-600F aircraft.

Variants of the Airbus A300

A300B1

The two A300B1 prototypes were 51 m (167 ft) long. The A300B1 was the first variant to take off. It had a maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 132 t (291,000 lb), was 51 m (167 ft) long, and was powered by two General Electric CF6-50A engines. Only two prototypes of the variant were built before it was adapted into the A300B2, the first production variant of the aircraft. The second prototype was leased to Trans European Airways in 1974.

A300B2

The A300B2 was 53.6 m (176 ft) long, 2.6 m (8.5 ft) longer than the A300B1.

A300B2-100

Responding to Air France’s need for more seats, Airbus decided that the first production variant should be larger than the original A300B1 prototype. The CF6-50A-powered A300B2-100 was 2.6 m (8.5 ft) longer than the A300B1 and had an increased MTOW of 137 t (302,000 lb), allowing for an additional 30 seats and raising the typical number of passengers to 281, with capacity for 20 LD3 containers. Two prototypes were built and the variant made its maiden flight on June 28, 1973, was certified on March 15, 1974 and entered service with Air France on May 23, 1974.

A300B2-200

For the A300B2-200, originally designated the A300B2K, Krueger flaps were introduced at the root of the leading edge, louver angles were reduced from 20 degrees to 16 degrees, and other elevation-related changes were made to introduce a high lift. This was done to improve performance when operating at high-altitude airports, where the air is less dense and lift generation is reduced. The variant had an increased MTOW of 142t (313,000 lb) and was powered by CF6-50C engines, was certified on 23 June 1976 and entered service with South African Airways in November 1976. The CF6-50C1 and CF6 models -50C2 were also installed later depending on customer requirements, these were certified on February 22, 1978 and February 21, 1980 respectively.

A300B2-320

The A300B2-320 introduced the Pratt & Whitney JT9D engine and was powered by JT9D-59A engines. Retaining the 142 t (313,000 lb) MTOW of the B2-200, it was certified on January 4, 1980, and entered service with Scandinavian Airlines on February 18, 1980, with only four produced. The total of the produced variants of the A300 family correspond to: A300B2-100 32 units, A300B2-200 25 units, A300B2-320 4 units.

A300B4

The A300B4-100 took off for the first time on December 26, 1974, it maintained the length of the B2 but featured a greater fuel capacity.

A300B4-100

The initial variant of the A300B4, later called the A300B4-100, featured a center fuel tank for increased fuel capacity of 47.5 tonnes (105,000 lb), and had an increased MTOW of 157.5 tonnes (347,000 lb). It also featured Krueger flaps and had a high lift system similar to that later fitted to the A300B2-200. The variant made its first flight on December 26, 1974, was certified on March 26, 1975 and entered service with Germanair in May 1975.

A300B4-200

The A300B4-200 had an increased MTOW of 165 tonnes (364,000 lb) and featured an additional optional fuel tank in the rear cargo hold, which would reduce cargo capacity by two LD3 containers. The variant was certified on April 26, 1979. The B4 variant has been produced in two versions: A300B4-100 with 47 units, A300B4-200 with 136 units.

A300-600

With small wingtip fences, the A300-600 entered service in June 1984 with Saudi Arabian Airlines. The A300-600, officially designated the A300B4-600, was slightly longer than the A300B2 and A300B4 variants and had greater interior space by using a rear fuselage similar to the Airbus A310, this allowed it to have two additional rows of seats. It was initially powered by Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7R4H1 engines, but was later fitted with General Electric CF6-80C2 engines, with Pratt & Whitney PW4056 or PW4058 engines being introduced in 1986. Other changes include an improved wing with a trailing edge retreading, the addition of simpler single-slot Fowler fins, the removal of slat fences, and the removal of outboard ailerons after they were deemed unnecessary on the A310. The variant made its first flight on July 8, 1983, was certified on March 9, 1984 and entered service in June 1984 with Saudi Arabian Airlines. A total of 313 A300-600s (all versions) have been sold. The A300-600 has a similar cockpit to the A310, using digital technology and electronic displays, eliminating the need for a flight engineer. The FAA issues a single type rating that allows operation of both the A310 and the A300-600.

The A300-600 has had the official designation as A300B4-600. The reference model of the 600 Series. The A300-620C as the official designation A300C4-620, a convertible freighter version of which four units were delivered between 1984 and 1985. A300-600F as the official designation: A300F4-600, the version of 600 Series baseline load. The A300-600R as official designation: A300B4-600R with increased 600 Series range, achieved with an additional trim fuel tank in the tail. The first delivery in 1988 to American Airlines; all A300s built since 1989 (freighters included) are Series 600Rs. Japan Air System, later merged with Japan Airlines, took delivery of the last new-build passenger A300, an A300-622R, in November 2002. The A300-600RC with official designation A300C4-600R, the convertible freighter version of the 600R, with a delivery of two units in 1999. The A300-600RF with official designation A300F4-600R, the freighter version of the 600R. All A300s delivered between November 2002 and July 12, 2007 (last A300 delivery) were A300-600RFs.

A300B10 / A310

Airbus had a demand for an aircraft smaller than the A300 as a complement. On July 7, 1978, the A310, initially designated the A300B10, was launched under orders from Swissair and Lufthansa German Airlines. On April 3, 1982, the first prototype made its maiden flight and received its type certification on March 11, 1983. Maintaining the same eight-point cross section, the A310 is 6.95 m (22.8 ft) longer shorter than the initial A300 variants, and has a smaller 219 m 2 (2,360 sq ft) wing, down from 260 m 2 (2,800 sq ft). The A310 introduced a two-crew glass cabin, later adopted for the A300-600 with a common type classification. It was powered by the same GE CF6-80 or Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofans as the PW4000. It seats 220 passengers in two classes, or 240 in all economy classes, and can fly up to 5,150 nmi (9,540 km). It has wing outlets between the two pairs of main front and rear doors. In April 1983, the aircraft entered revenue service with Swissair and competed with the Boeing 767-200, introduced six months earlier. Its longer range and ETOPS regulations allowed it to be operated on transatlantic flights. Until the last delivery in June 1998, 255 aircraft were produced, as it was succeeded by the larger Airbus A330-200. It has cargo aircraft versions, and was derived into the Airbus A310 MRTT tanker/military transport.

A300-600ST

The Airbus Beluga is based on the A300 with a large cargo hold on top. Commonly known as the Airbus Beluga or Airbus Super Transporter, these five airframes are used by Airbus to transport parts between the company’s disparate manufacturing facilities, enabling shared work distribution. They replaced the four Aero Spacelines Super Guppies previously used by Airbus.

A300, precursor to Airbus

As of June 2022, there were 229 A300 Family aircraft in commercial service. The five largest carriers were FedEx Express (70), UPS Airlines (52), European Air Transport Leipzig (22), Mahan Air (13), and Iran Air (11).

The A300 line has been the first widebody commercial aircraft with the character of competing with the main industrial companies in the world, allowing it to break with the hegemony of the commercial aviation industry. Airbus has managed to conquer the skies for the first time in October 1972, a project that had been born under enormous skepticism, reaching air supremacy thanks to its A300 model, fifty years after its first flight. ![]()

PUBLISHER: Airgways.com

DBk: Airbus.com / Wikipedia.org / Airgways.com

AW-POST: 202210301711AR

OWNERSHIP: Airgways Inc.

A\W A I R G W A Y S ®